The international community can no longer ignore the alarming rise in violence directed at Pakistan’s Shia minority.

By Waris Husain

Last month the world commemorated the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide. Dignitaries from around the world delivered speeches to mark the occasion, but UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon’s statement was perhaps the most remarkable, as he admitted that the United Nations was “ashamed” of its failure to prevent the mass killing. At the same time Ban was making this statement, a Shia doctor was gunned down in Karachi, Pakistan by sectarian terrorists, as part of a self-avowed campaign to “make Pakistan a graveyard” for all Shias.

Despite the escalation of targeted killings of Shia leaders and large-scale bombings of Shia neighborhoods, the Pakistani government and international community have failed to apply the lessons from cases like Rwanda in recognizing the early warning signs of an impending genocide perpetrated by sectarian terrorist groups. While the murder rates of Shias in Pakistan is nowhere close to the 800,000 Tutsis killed in Rwanda, members of the international community are duty-bound to prevent mass killing events before they occur.

The Shia’s plight must be understood in the context of Pakistan’s position within the larger sectarian struggle between Sunnis, largely supported by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, and Shias, supported by Iran and its close allies. Pakistan walks a tightrope in this conflict as it shares a border with Iran, but relies on Saudi Arabia for aid and political patronage. This international tension has domestic implications with 20 percent of Pakistan’s population belonging to the Shia faith, amounting to nearly 25 million people who are being threatened with extermination by sectarian outfits.

To understand the threat that Pakistan’s Shias face, one must look to the Convention on the Punishment and Prevention of Genocide, to which Pakistan is a signatory. Under the Convention, a genocide occurs when a party has the intent to destroy a religious, ethnic, or racial group “in whole, or in part” and acts on that intent by killing, injuring, or deliberately causing conditions leading to the physical destruction of that group.

The Convention applies to all people, including private groups that are perpetrating genocidal acts in a country without direct assistance from the state. Under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), all countries are obliged to recognize if such acts are taking place and take steps to punish past transgressions while preventing future acts.

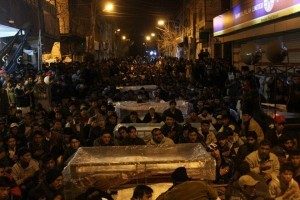

In the context of Pakistan, the two elements to prove genocide are clearly satisfied: terrorist groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) have openly committed brutal murders of Shias with the self-avowed purpose of “cleansing Pakistan” of their presence. The attacks against Shias have basically taken three forms. First, high profile community members like doctors, lawyers and judges have been targeted in drive-by shootings in Karachi. Second, Shia religious processions and pilgrims have repeatedly been targeted in mass-shooting attacks. Third, Hazara Shias have been attacked en-masse in the city of Quetta, with several car bombings that have left hundreds dead in the last three years.

This has led to a mass exodus of Hazaras from Balochistan, with as many as 30,000 leaving the province over the last five years, according to some estimates. Many have left because they believe the government refuses to acknowledge the concerted campaign against them, and is therefore not taking steps to protect them.

Sectarian groups like Laskar-i-Islam (LI) and LeJ use various methods to terrorize Shias and force them to leave their homes, including the distributing threatening pamphlets, as occurred in Peshawar on April 16, 2014. Further, these groups often accept responsibility for vicious attacks on Shias, and express their genocidal intent in promising future attacks. This was certainly the case when the “Principal of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi” issued an open letter declaring that all Shias were “wajib-ul-katl” or “worthy of killing” in the aftermath of an attack that left eight Hazaras dead.

Despite these openly violent assertions, the government of Pakistan continues to deny the existence of genocide against Shias. As such, there are no official statistics on the number of victims, which would be a key component in understanding the level and frequency of violence perpetrated by sectarian militants. It is difficult to assess the level of political or military support these sectarian groups enjoy; however, there are a few issues that have raised concern in the past.

First, the Pakistani judiciary has been woefully ineffective at punishing acts of terrorism, especially when the victims were religious minorities. One need only look to the case of Malik Ishaq, a co-founder and leader LeJ, who has been arrested and released from jail several times, despite being implicated in the murder of hundreds of Shias. Sectarian groups often target judges and prosecutors in order to intimidate the court and its officers.

Second, many blame Islamist dictator General Zia Ul-Haq for creating these sectarian militant groups to use as proxies in Kashmir and Afghanistan in the 1980s. The groups have long since turned their violence inward toward Pakistan’s religious and ethnic minorities. Many fear the pattern from the 1980s may now be repeating itself as Syria witnesses an influx of Pakistanis entering the country to fight alongside anti-Shia militant groups opposing the Bashar al-Assad government. This could wreak havoc on Pakistan when these battle-hardened operatives return home and turn their guns on the nation’s minorities, especially Shias.

Additionally, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, a Zia protégé, has been accused of being soft on these groups while leading his socially-conservative political party, the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN). This claim was given credence by the fact that the PMLN was distributing a monthly stipend to Malik Ishaq’s family while Ishaq was in jail for one of his forty-four different criminal charges relating to 70 murders, many of them Shias.

Further, some also believe that anti-Shia rhetoric is seeping into the mainstream of politics. For example, Maulana Ludhanvi, the leader of the Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) recently won a national assembly seat. In campaigning for the seat, Ludhanvi promised, “At the moment I can raise a voice for my anti-Shia mission only at a local level and from my local mosque. But when I get the microphone in the [National] Assembly, the whole nation and the whole world will listen…”

All of these examples are consistent with the early warning signs of genocide identified by international legal scholars like Barbara Harff, who created an analytical rubric that examines “trigger events” for genocide, such as assassinations of community leaders, impunity for genocidal actors, or political instability. Accordingly, in her annual Global Watch List, Harff has repeatedly identified Pakistan as a high-risk country for mass killings targeting religious minorities, including the Shia community.

Even though the administration has not openly acknowledged the potential for genocide against Shias, there are indications that the government, or parts of it, is taking note of the growing problem. For example, the Ministry of Interior recently admitted to the Senate that more than 2,000 Shias have been killed in sectarian attacks over the last five years. Similarly, Punjab provincial police have recently begun targeting “sectarian outfits,”which has already resulted in the arrest of suspects believed to be involved in eighteen attacks that left 16 Shias dead. Furthermore, the government is in the process of passing anti-terror legislation like the Pakistan Protection Ordinance and the Fair Trial Act, which could be used to effectively prosecute sectarian militants in the future.

Pakistan and the international community at large have a responsibility to protect populations vulnerable to genocidal acts, and the first step towards this protection is realizing the scope of the problem. If the government of Pakistan were to recognize that anti-Shia attacks are early warnings of a campaign that has the potential to endanger the lives of more than 20 million Shia citizens, it could begin collecting official statistics on Shia murder rates. It could also use already existing legislation criminalizing hate-crimes to prosecute members of these groups. In addition, the government could utilize the powers that were recently granted to it under the anti-terror laws to tackle the sectarian violence.

At the same time, the international community could assist with resources and scholarly advice while applying diplomatic pressure to force Pakistan’s government to more vigilantly punish and prevent anti-Shia campaigns by terror groups. If the UN is truly “ashamed” of its failure to prevent the genocide in Rwanda, it must use early warning signs and diplomatic pressure to abide by the mantra of genocide prevention: “Never again.”